The fall of the Berlin Wall was a distant event for many — oceans away on TV screens and newspapers — but, for a high-school-aged Ellie Pojarska, it meant the possibility of an education in the United States.

Pinewood American Literature Honors Teacher Pojarska grew up under the Iron Curtain in Bulgaria, a country dominated by communist politics. According to Pojarska, the culture funneled kids down a particular path at a young age. At 14, she had to choose between pursuing rhythmic gymnastics or her love of language and writing.

She chose the latter, enrolling in a language school for the next three years. There, she eriously studied English for the first time, beginning a journey that would eventually put Italian, Latin and German under her belt as well.

When the Iron Curtain fell in 1989, Pojarska leapt at the chance to leave Bulgaria, applying for a scholarship through the George Soros foundation.

She made her way to Monroe-Woodbury High School, a large public school in New York, where she was inspired by her AP English teacher to eventually become a teacher herself. However, once Pojarska graduated early, she was required to return to Bulgaria.

There, she was attending the American University in Bulgaria, when her dad entered her name in a green card lottery that sought to bring more Eastern European diversity to the United States. In a stroke of luck, she received the green card and was just old enough to travel to the states on her own.

After returning to America, she attended the University of Montana for her bachelor’s and master’s before receiving a second master’s at Stanford University.

“To be honest, the best teachers I had were at the University of Montana,” Pojarska said. “I think it was because those people were focused on teaching more than research. I learned, especially during my time at Stanford, that teaching was not even spoken about because research was the focus.”

She was on a path to become an expert in 16th Century literature after years of research at Stanford, but did not want to be limited to this genre for the rest of her career. As a result, Pojarska pursued jobs in teaching, spending a year at Castilleja as a substitute teacher.

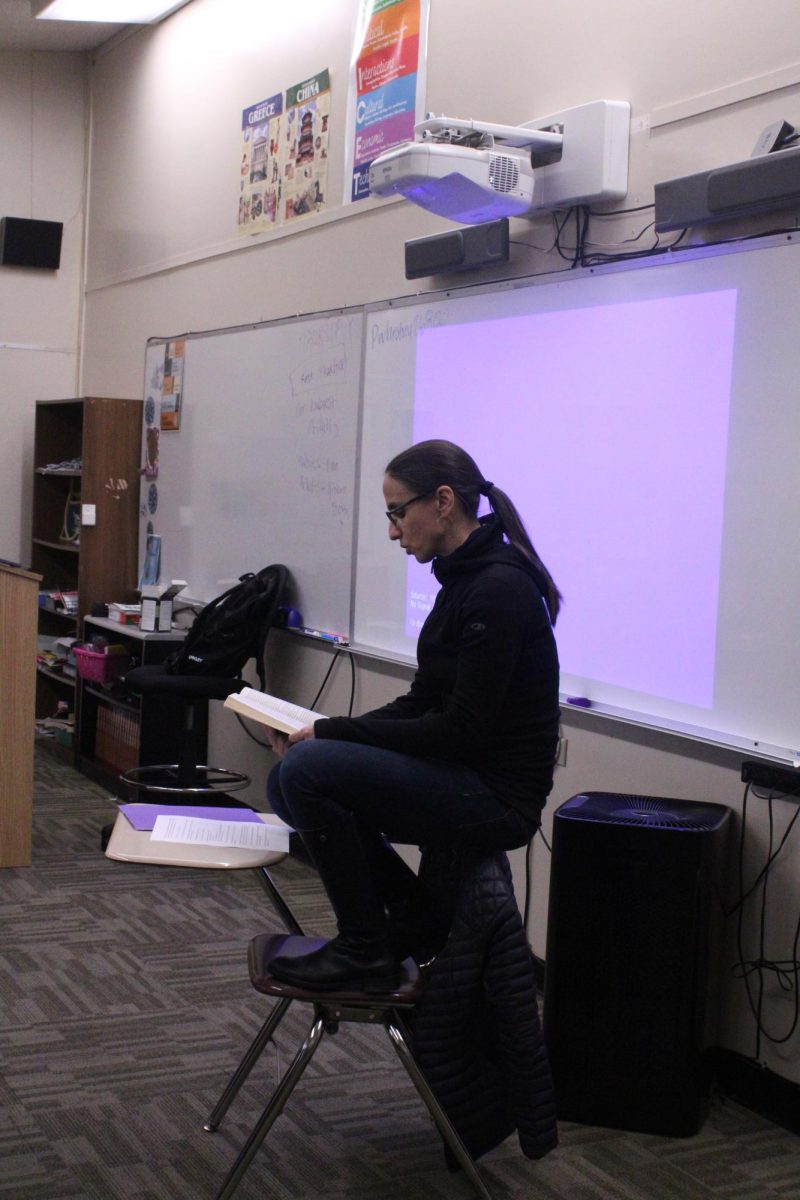

Pinewood called her during the summer to take on a part-time job as an 11th grade British Literature teacher. She accepted the role and began to shape her teaching style, taking a different approach than her childhood teachers in Bulgaria.

“I grew up in an environment myself where we were not given much freedom and were basically told to just regurgitate the text we were learning,” Pojarska said. “It has been my mission in life to do the exact opposite of that.”

Pojarska centers her class around student-led discussions where she guides students to find the answers themselves rather than laying down the law of the text with an iron fist.

“I think that it is a lot more beneficial to you to struggle through the interpretation yourself,” Pojarska said. “It is important to be comfortable with ambiguity and see things that may be contradictory.”

Pojarska has worked to accommodate students who are both loud and quiet, those who like math and those who like writing and those who are engaged with one book more than another, learning from her own children’s proclivities toward different subjects.

“I have one kid at home who is really into science and math and all that, and I have to think how what I am doing in class would engage that type of kid,” Pojarska said. “I have another kid who is very precisely engaged in humanities, and I worry that in my class she would get bored out of her mind.”

According to Pojarska, to an extent, students should participate to the degree that they feel comfortable, but they should also challenge themselves to do the opposite of what they are inclined to do.

“For example, I would challenge a more talkative kid to listen more and a quieter kid to participate more often,” Pojarska said. “But I do still have a lot of empathy for the quiet kids because I was one myself.”

After going through college admissions with her son, Pojarska has noticed how students have gotten busier, taking on many extracurricular activities to boost a college application. She has become mindful about the amount of work she assigns, but can still see the impact that the stress of college has on students’ mental health.

“I go through periods of rage about it as a parent,” Pojarska said. “I feel like the college process is almost this invisible force. It’s like an invisible cultural juggernaut that is just crushing all of us.”

According to Pojarska, the landscape of college admissions, along with cultural differences between her childhood peers in Bulgaria and her students in the United States, has changed the students themselves, giving them more depth at the price of an unmanageable schedule.

“There are educational systems around the world that base college admissions on just grades and final exams,” Pojarska said. “America is unique. I think that a lot of you are more interesting people than the people I grew up with.”